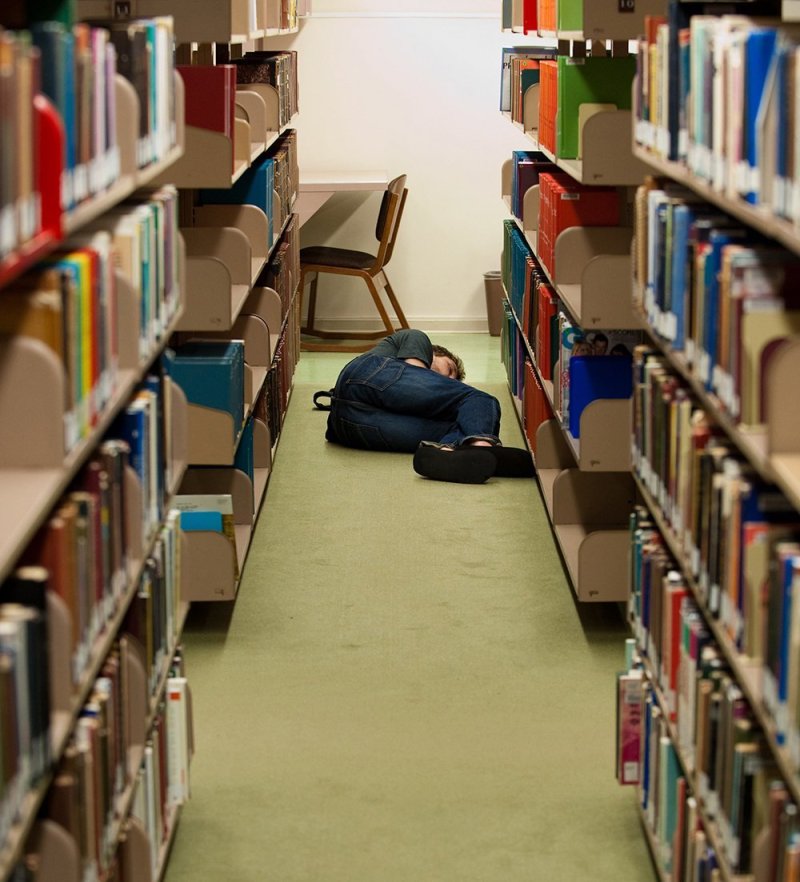

The sleep-deprived college student is a common trope. But today’s college students aren’t just pulling all-nighters and prioritizing social life over sleep. Many are working while going to school, engaging in social media into the wee hours, and answering texts throughout the night. And their adult role models are hardly setting a better example. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has even gone as far as calling sleep deprivation in the United States an “epidemic.”

How serious is the issue of sleep deprivation? Is working or studying until 3 a.m. a badge of honor or a mistake? Despite a public penchant for coffee-fueled survival, the truth is that lack of sleep — especially chronic sleep deprivation — can have serious, even life-threatening effects.

Despite the risks, many people simply are not prioritizing sleep. More than 700 PLNU students took part in the 2017 American College Health Association National College Health Assessment II. When it came to sleep, the results were troubling. While about 50 percent of students met national exercise goals, less than 10 percent said they got enough sleep to feel rested every night. In fact, 32 percent said they only got enough sleep to feel rested once or twice a week. Only 8 percent reported no problems with daytime sleepiness in the last week. About 46 percent said daytime sleepiness was “more than a little problem,” “a big problem,” or “a very big problem.”

__________

Experience life-changing education.

Connect with PLNU.

__________

And, as noted, it’s not just college students. Studies show that more than half of Americans are regularly sleep deprived. The CDC recommends that healthy adults aged 18 to 60 sleep seven or more hours per night. Unfortunately, many people do not meet this goal, especially during the workweek.

Sleep and Daily Functioning

Most everyone knows the dragging feeling that can come after a poor night’s sleep. PLNU professor of biology David Cummings, Ph.D., explained it this way: “When you’re under-rested you have the feeling that something is wrong; it’s almost a toxic feeling, and research shows that it is.”

Studies show that both memory and learning are impacted by sleeping less than needed.

“Learning is about consolidating memories,” Cummings explained.

While a lack of sleep contributes to poor concentration and reduced effectiveness, conversely good sleep can help memory. According to the National Sleep Foundation, short-term experiences are cemented into long-term memories during sleep. What’s more, sleep is essential for optimal focus, and focus is vital for learning. This process requires time spent in both REM and non-REM sleep cycles, according to Cummings. For students, understanding how sleep is vital to achieving their goals could be a motivator to prioritize rest.

When you’re under-rested you have the feeling that something is wrong; it’s almost a toxic feeling, and research shows that it is.

“If you are trying to learn things to change how you will be as a Christian, a person, a worker, and if you want to be good at what you do, you need good sleep before the learning and that very night after,” he explained. “You don’t retain nearly as much if you don’t sleep. All nighters don’t fit the biology of learning.”

Even for adults whose jobs don’t require constantly learning new things, short sleep can lead to errors and poor concentration. For hospital workers, pilots, and others, errors on the job can cost far more than time or reprimands.

An article entitled “Effects of sleep deprivation on procedural errors,” published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, reported that in a recent study “Sleep-deprived participants were more likely to suffer a general breakdown in ability (or willingness) to meet a modest accuracy criterion they had met the night before. Among sleep-deprived participants who could still perform the task, error rates were elevated, and errors reflecting memory failures increased with time-on-task.”

This news is hardly shocking. According to the National Sleep Foundation’s 2018 Sleep in America poll, “A majority of American adults (65%) think sleep contributes to next day effectiveness. Great sleepers realize the benefit, yet only 10% of people prioritize it over other aspects of daily living.”

Work and school performance aren’t the only areas where sleep deprivation impairs daily functioning. The CDC issued a statement this year explaining that drowsy driving can be as dangerous as driving under the influence of alcohol. The report said that “being awake for at least 18 hours is the same as someone having a blood content (BAC) of 0.05%” and “being awake for at least 24 hours is equal to having a blood alcohol content of 0.10%. This is higher than the legal limit (0.08% BAC) in all states.”

Several studies have shown that people who get less than five or six hours of sleep a night are up to four times more likely to catch a cold. This makes sense since deep sleep is vital to proper immune system functioning. People who are sleep deprived are also more likely to experience anger and frustration and are less resilient and less able to cope with stress.

Sleep and Disease Risks

Beyond these short-term risks of sleep deprivation are also significant long-term physical and mental health effects. According to the CDC, “Notably, insufficient sleep has been linked to the development and management of a number of chronic diseases and conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and depression.”

Sleep deprivation can increase hunger cues, making it harder for people to maintain or lose weight. At the same time, fatigue from lack of sleep decreases people’s drive to exercise and makes the body inefficient at calorie burning. All of these factors can contribute to obesity, which then becomes its own risk factor for other diseases. And, unfortunately, obesity can have a further negative impact on sleep since it increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

The connection between type 2 diabetes and sleep appears to be related to the body’s handling of glucose. According to the National Sleep Foundation, “after sleeping just four hours a night for a week, otherwise healthy people’s ability to break down sugars becomes 40 percent lower than normal—similar to those who don’t make enough insulin and are at risk for diabetes.”

Sleep is important in regulating hormones, which in turn are responsible for regulating blood glucose. Recurrent sleep loss leads to a lower production of insulin, which regulates blood sugar, and increased cortisol. While cortisol, a stress hormone, is effective at keeping a person awake, it further impairs insulin function. In combination, there can be a significant impact on the body’s ability to regulate glucose, which can lead to diabetes. Along with diet, weight, and family history, insufficient sleep can be a serious risk factor for the disease.

Recent scientific studies suggest that there may also be a link between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease.

Recent scientific studies suggest that there may also be a link between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Poor sleep has been found in several studies to increase the presence of beta amyloid proteins and tau proteins in the brain and spinal fluid. Both of these proteins have been linked to Alzheimer’s. It appears that REM sleep helps clear these and other toxins from the brain. Though more research is needed, experts hope that treating sleep problems could help prevent or delay dementia and Alzheimer’s in at least some people.

Sleep and Mental Health

Sleep and mental health are intricately intertwined. According to an article by Harvard Health, “Chronic sleep problems affect 50% to 80% of patients in a typical psychiatric practice, compared with 10% to 18% of adults in the general U.S. population.” Among those most affected are people with anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the article notes.

It goes on to explain that between 65 and 90 percent of people with depression also suffer from insomnia. This is especially troubling because “Depressed patients who experience sleep disturbances are more likely to think about suicide and die by suicide than depressed patients who are able to sleep normally.” Among people with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), more than 50 percent also have a sleep disorder. Extreme sleep deprivation can even lead to psychosis.

Cummings notes that the brain still holds many mysteries scientists don’t yet understand. Harvard Health explains how this relates to sleep and mental health:

“The brain basis of a mutual relationship between sleep and mental health is not yet completely understood. But neuroimaging and neurochemistry studies suggest that a good night’s sleep helps foster both mental and emotional resilience, while chronic sleep disruptions set the stage for negative thinking and emotional vulnerability.”

While much remains to be learned, the Harvard article reports that “sleep disruption — which affects levels of neurotransmitters and stress hormones, among other things — wreaks havoc in the brain, impairing thinking and emotional regulation. In this way, insomnia may amplify the effects of psychiatric disorders, and vice versa.”

Cummings has experienced the troubling pairing of sleep loss and anxiety himself.

“A few years ago, I basically hit a point of burnout,” he said. “I had been at the university for 10 years, and I had not been taking good care of myself. I had no good coping skills — I just tried to tough it out.”

The result in Cummings’ case was physical illness with a psychological basis.

“My body started breaking down,” he said. “I got physically ill, and it took a couple months of doctors ruling out the scariest biological possibilities — before I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and depression caused or exacerbated by chronic stress.”

Our culture devalues sleep and sees it as a sign of weakness,” he said. “We really need to shift our thinking as a culture.

Cummings said the acute phase of his GAD lasted about six months. In the years that have followed, he has aimed to learn more about the biology and psychology of mental health as well as to understanding it from a spiritual perspective.

“Our culture devalues sleep and sees it as a sign of weakness,” he said. “We really need to shift our thinking as a culture. Sleep is just as important as diet, exercise, and hydration. Since I have been trying to prioritize sleep, it has made a very big difference.”

Improving Sleep

It seems like a simple problem to solve: if sleep is important and we aren’t getting enough, we should just sleep more. But simple doesn’t always mean easy. Some people don’t get enough sleep due to poor habits that they may be able to change; others struggle with insomnia or health issues that impair sleep. There is also data that shows that socioeconomic factors can affect sleep. For those who do have the ability to address sleep-related behaviors, Cummings agrees with experts that some basic “sleep hygiene” practices can be helpful.

Recommendations from Harvard Health include going to bed and waking up at the same time each day, including weekends; avoiding alcohol and caffeine, especially near bed time; completing exercise at least two hours before bedtime; and keeping bedrooms cool, dark, and quiet. Cummings also notes that it is helpful to turn off technology one to four hours before sleep because light can interfere with our natural sleep-wake cycles, called circadian rhythms.

“Avoiding blue light or any light before sleep is about trying to keep circadian rhythms intact,” Cummings said. “Light is the primary controller of our circadian rhythms. When you get up in the morning, go outside, open window coverings, etc. This helps you biologically transition over to wake cycles. As for bedtime, getting rid of lights, and phones more than anything, can help.”

For those with more persistent sleep issues, cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to be a helpful option for insomnia. Medications are also available. For those with anxiety or depression, treating both the mental health issue and the sleep disorder at the same time can help both issues at once.

What’s clear is that working to improve sleep is worthwhile.

Charley Hardison, M.D., sees students in PLNU’s Wellness Center for a variety of medical needs. He works closely with other providers, including PLNU’s counselors. Sleep has become an increasingly important factor on Hardison’s radar as he works with students, especially those who have symptoms that may be related to stress or mental health.

“We have had dramatic results helping people with getting adequate rest,” he said. “Sleep relates to performance, satisfaction, a sense of well-being, anxiety, and depression.”

Good sleep — meaning appropriate length, quality, and consistency — fosters resilience. Poor sleep favors negative thinking and vulnerability or reactivity.

Cummings explains why Hardison’s sleep prescription helps: “Good sleep — meaning appropriate length, quality, and consistency — fosters resilience. Poor sleep favors negative thinking and vulnerability or reactivity.”

Hardison says it’s not difficult to see why students suffer with maintaining healthy sleep routines. Just like working adults who often short-change their sleep during the week in exchange for greater productivity or the pursuit of downtime, college students have many things competing with their physiological need for sleep.

“Roommates, stress, the demands of college, screen time,” he said. “It’s a spiritual discipline to be still and to meditate and to listen and to rest.”

While we may not always be able to fall asleep on command, we can respect the biblical calls to rest and not to put earthly toils above the physical need for sleep God created in us.

About the Author

Christine Spicer is the editor of the Viewpoint magazine at PLNU.