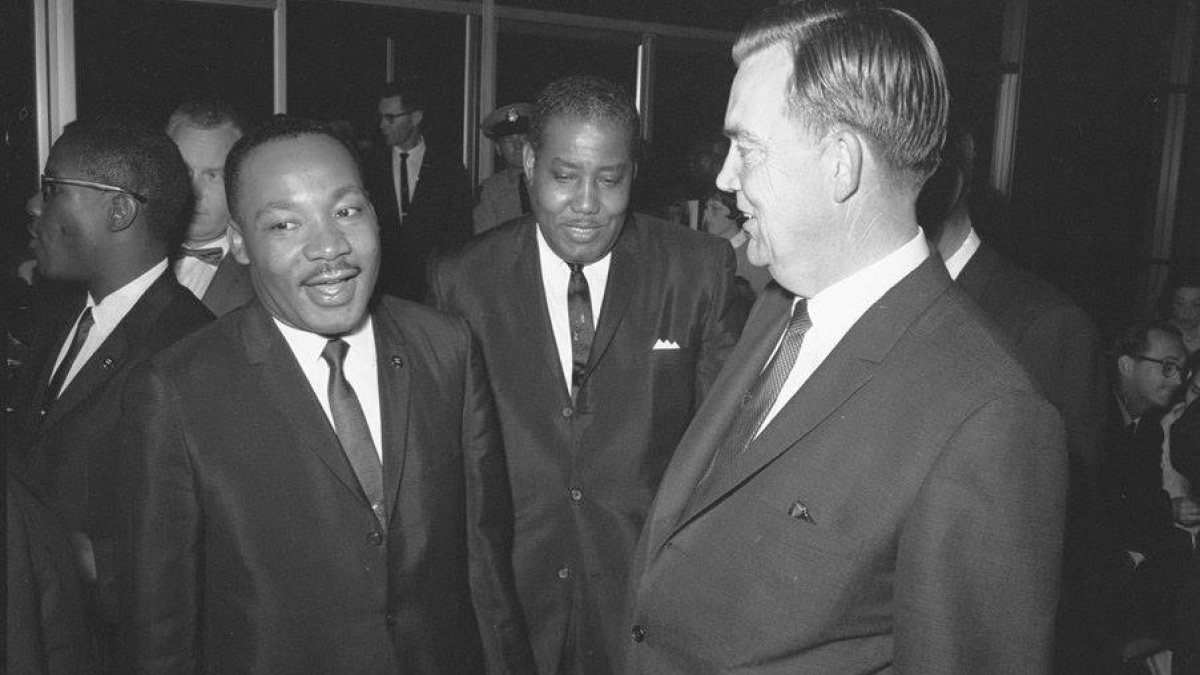

On May 29, 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited San Diego to speak at the campuses of San Diego State University and Point Loma Nazarene University (then Cal Western University).

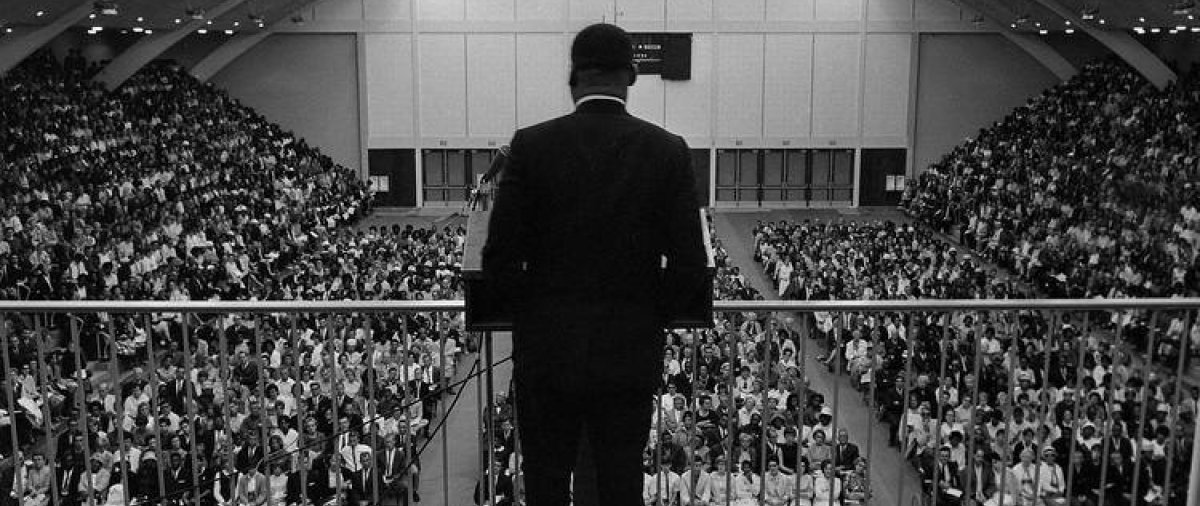

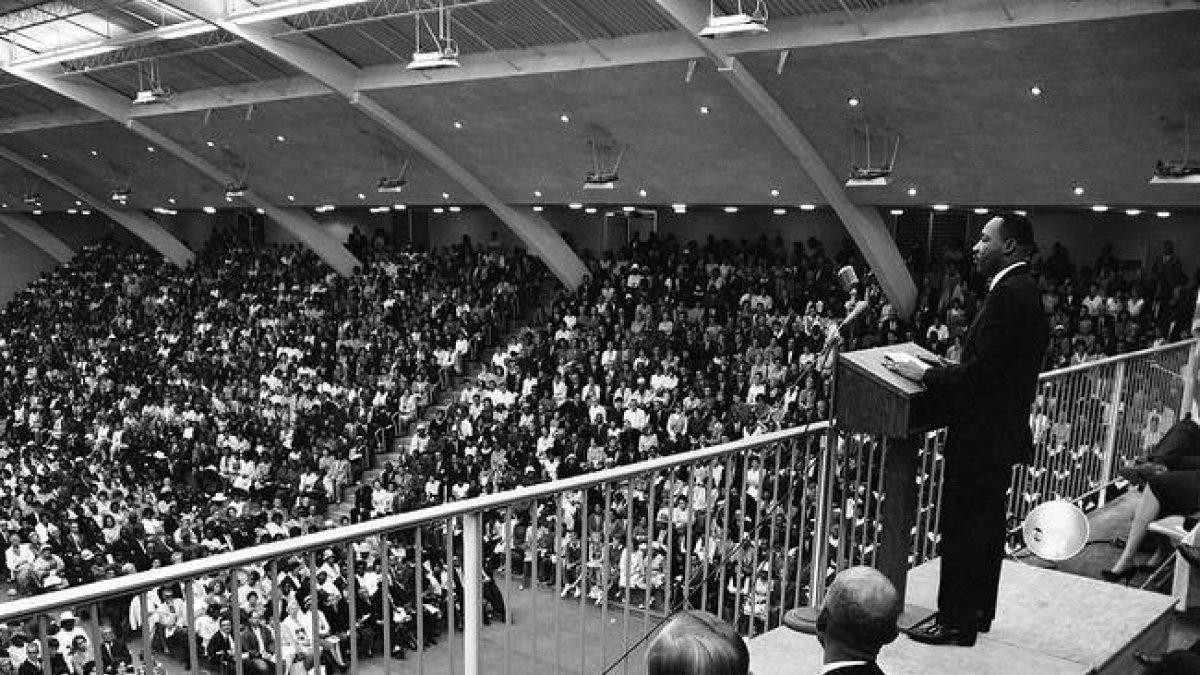

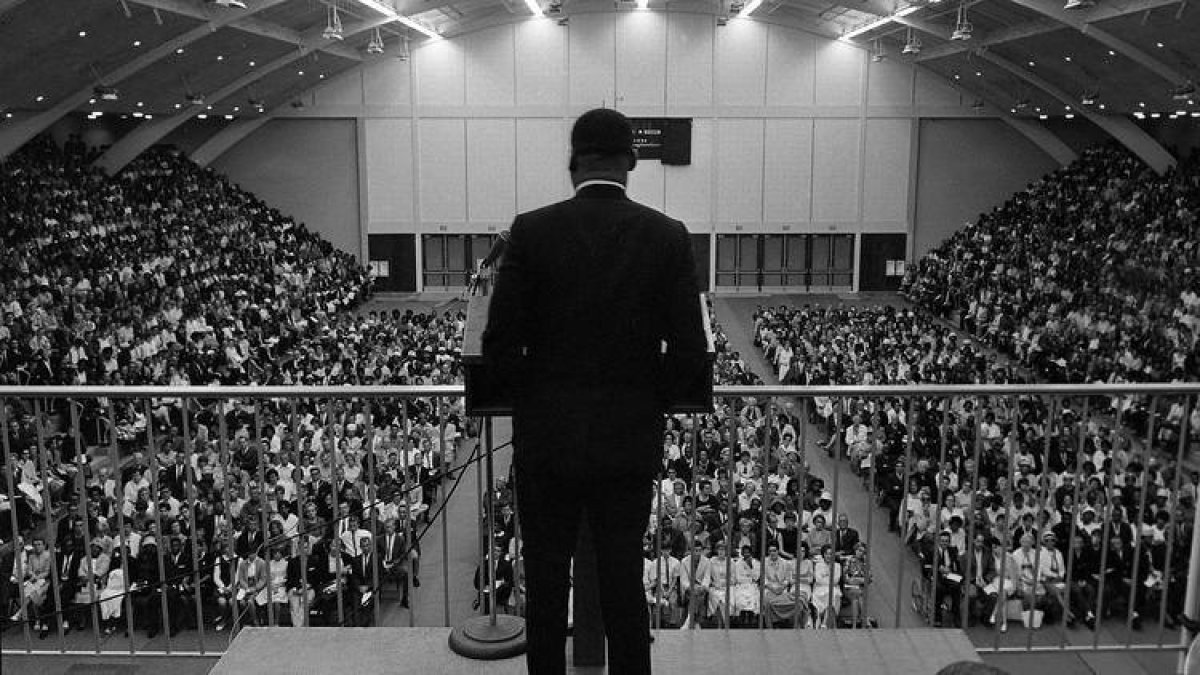

Less than a year after the March on Washington and his famous I Have a Dream speech, Dr. King stood in what is now PLNU’s Golden Gymanisum to deliver his speech Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution to advocate for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and against Proposition 14 to repeal the Fair Housing Act of 1963 — issues that remain relevant to this day.

The legacy of Dr. King’s visit to the PLNU campus is honored with a podium, audio of his speech, and photography that can be viewed where he stood in PLNU’s Golden Gym.

Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution

Below is the transcript of the full speech delivered by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at PLNU's Golden Gymnasium on May 29, 1964.

Ladies and gentlemen, I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to have the opportunity of coming once more to the city of San Diego, California, and the opportunity of being a part of this meeting. It is always a rich and rewarding experience when I can take a brief break from the day-to-day and hour-to-hour demands of our struggle in the South, and discuss the issues involved in that struggle with concerned people all over this nation and all over the world. And I want to express my deep personal appreciation to all of the sponsoring groups this evening for making this magnificent meeting possible. I say this magnificent meeting because you have turned out in such large numbers, and I am sure that your presence here tonight is indicative of your support and your concern in the area of civil rights. Certainly, we need that support in this hour and at this period in our nation’s history. And I can assure you that I am deeply inspired as I look out into your faces and as I notice this beautiful, integrated audience. It gives me deep joy within. I wish you could see yourselves and look how beautiful you look. And somehow this is what mankind should be and how mankind should look one day in our nation all over this vast land. We will come to see integration not as a problem, but as an opportunity to participate in the beauty of diversity. And so it is great and noble to have the privilege of being here tonight and I bring greetings to you from all of the members, all of the officers, and all of the staff members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference who are working all over the Southland to make justice and freedom a reality in that section of the country.

We have our difficult moments as you well know. In fact, I just talked with some of our staff members who are now in St. Augustine, Florida. Four of us who are here tonight just left there a few hours ago, and not long after we left they shot in the house some fifteen times where we were staying. They thought we were there, I guess, last night. Fortunately, nobody was in the house, because if we had been there somebody may have faced physical death. We work under these conditions all along and yet we do it without fear. We do it with a determination to go on because the destiny of our nation is involved and we are struggling not merely to free twenty million Negroes but we are struggling to free the soul of our nation.

I am so happy that the religious forces of this community and of this state have participated in such a meaningful way by serving as a sponsoring organization for this particular meeting and the other meetings that I will be addressing in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno before returning to the South. It is good to see this because as you know this problem is a moral problem. And the religious institutions, being the moral guardians of the community, must certainly take a great responsibility in making brotherhood a reality.

This evening I would like to discuss some of the problems that we still face in our nation in the area of race relations and reiterate some of the things that I said earlier in the afternoon at San Diego State [University] by using as a subject from which to speak Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution. Many of you have probably read that arresting little story by Washington Irving entitled Rip Van Winkle. The thing that we usually remember about Rip Van Winkle is that he slept twenty years. But there is another point in that story that is almost always completely overlooked. It was a sign on the inn in the little town on the Hudson in which Rip went up into the mountain for his long sleep. When he went up the sign had a picture of King George the Third of England. And when he came down the sign had a picture of George Washington, the first President of the United States. And when Rip looked up at the picture of George Washington he was amazed. He was completely lost. He knew not who he was. This incident reveals to us that the most striking thing about the story of Rip Van Winkle is not merely that he slept twenty years, but that he slept through a revolution. While he was peacefully snoring up in the mountain, a great revolution was taking place in the world; a revolution that at many points would change the course of history. And yet, Rip Van Winkle knew nothing about it. He was asleep. One of the great liabilities of history is that all too many people find themselves amid great periods of social change and yet they fail to achieve the new mental outlook, and the new attitudes, that the new situation demands. All too many people find themselves sleeping through a revolution. And I am convinced that there is nothing more tragic than to sleep through a revolution. There can be no gainsaying of the fact that a revolution has taken place in the world and in our nation and is sweeping away an old unjust order and bringing into being a new creative order. The great challenge facing every man and every woman today is to remain awake through this great social revolution.

Now I would like to suggest some of the things that we must do here in America if we are to remain awake through this revolution. First I would like to say that we must reaffirm the essential immorality of racial segregation. Whether it is the legal de jure segregation of the South or whether it is the de facto segregation of the North, we must come to see that segregation is morally wrong and sinful. It is not only politically unsound. It is not only sociologically untenable, but segregation is morally wrong and sinful. Segregation is wrong because it is nothing but a new form of slavery covered up with certain niceties of complexity. Segregation is a cancer in the body politic which must be removed before our moral health can be realized. And I have come to see this over and over again in so many instances.

I remember not too long ago that Mrs. King and I had the privilege of journeying to that great country known as India. As we traveled all over the country hundreds and thousands of people followed us, everywhere we went, not so much because we had anything unique to say, but because we were Negroes in the United States (from the United States, rather), and they wanted to hear about the race problem. I never will forget one afternoon we journeyed to the southernmost part of India, the state of Kerala, the city of Trivandrum. And I was to speak that afternoon in a school that was attended largely by students whose parents were considered untouchables. Now in India the problem of caste untouchability is similar to the problem that we face in race relations in the whole area of segregation. Untouchables for years were considered inferior and they could not use certain public facilities. They could not go into the temples. They were considered outcasts. And that afternoon as I entered into the auditorium to make my speech, the principal introduced me. And after he said several things he finally said to the students, I would now like to introduce to you a fellow untouchable from the United States of America.

For the moment I was a bit peeved and shocked that I would be referred to as an untouchable. In that moment my mind leaped back across the mighty Atlantic and I started thinking about the fact that in Montgomery, Alabama, where I was living at that time, I could not go to any restaurant that white people had the privilege of going to. I could not go to a lunch counter and get a hamburger or a cup of coffee. I started thinking about the fact that even if I wanted to gain the great insights of the ages, in going to the public library, I couldn’t go because it was for whites only. I started thinking about the fact that I could not go to a single public park in Montgomery, Alabama, because all of the parks were closed as a result of a court order calling for integration of recreational facilities. And I started thinking about the fact that my little daughter and other children that would be born in our family would be raising nagging questions, “Why is it that we can’t go here? Why is it that we can’t go there?” And so deep down within I had to say to myself, “I am an untouchable and every Negro born in the United States is an untouchable.” And this is evil. And this is the evilness of segregation. It stigmatizes the segregated as an untouchable in a caste system. And so we must reaffirm the essential immorality of this system and we must make it clear all over the nation that segregation must go and that we are through with segregation now, henceforth, and forevermore.

Now the second thing that I would like to mention deals with a problem that we still find. It is in the ideological realm. It is the idea that there are superior and inferior races. We are challenged more than ever before to get rid of the notion that there are superior and inferior races. But anybody who believes this is sleeping through a revolution.

Now, certainly, we don’t need to sleep at this point. Great intellectual disciplines have pointed out that there is no truth in this. Great anthropologists like Ruth Benedict, Margaret Meade, the late Melville Herskovits, and others have made it clear over and over again that, as a result of their long years of study, they have found no evidence for this idea of superior and inferior races. There may be superior and inferior individuals within all racial groups, but there are no superior and inferior races. And yet in spite of this, many people still go along believing in this false notion. I was appalled to see as a result of a survey by Newsweek magazine a few months ago, the percentage of the white persons of this nation who believe that Negroes are inherently and biologically inferior. These people are sleeping through a revolution. Now there was a time that people used to try to justify the inferiority of the Negro on the basis of religion and the Bible. It’s tragic indeed how people will use religion, I should say misuse religion and the Bible, to justify their prejudices. And so it was argued that the Negro was inferior by nature, because of Noah’s curse upon the children of Ham. The Apostle Paul’s dictum became a watchword, “Servants, be obedient to your master.” And then one brother had probably read the logic of the great philosopher Aristotle. Aristotle was a philosopher who lived in the heyday of Greek culture. And he did a great deal to bring into being what we now know in philosophy as formal logic. And formal logic has a big word known as a “syllogism.” A syllogism has a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. And so this brother decided to put his argument of the inferiority of the Negro in the framework of an Aristotelian syllogism. He could say as his major premise, “All men are made in the image of God.”

Then came his minor premise, “God, as everybody knows, is not a Negro. Therefore, the Negro is not a man.” This was a kind of reason. But on the whole, we’ve gotten away from these arguments. Now not altogether because I read the other day that a brother down in Mississippi said that God was a charter member of the White Citizens Council. But there, seriously, we’ve gotten away from many of these arguments now and arguments are now on subtle sociological, cultural grounds. “The Negro is not culturally ready for integration.” You’ve heard these arguments. If you integrate the schools and neighborhoods this will pull the white race back a generation. And you see the Negro as a criminal. These arguments go on ad infinitum. And individuals who set forth such arguments never go on to say that if there are lagging standards in the Negro community, and there certainly are, they lag because of segregation and discrimination. Poverty, ignorance, social isolation, economic deprivation breed crime whatever the racial group may be. And it is a tortuous logic to use the tragic results of segregation as an argument for the continuation of it. It is necessary to go back to the cause of it. And so it is necessary to get rid of this notion once and for all.

Now if you would allow me I would like to say just a word to those of us who have been on the oppressed end of the old order. We’ve lived with the system so long. And when one lives with an evil unjust system so long, that is always a danger. That system generates a feeling of inferiority. And I think this is one of ultimate evils of segregation. Not merely what it does to one in terms of physical inconvenience, but what it does to one’s psychological makeup. And so it so often leaves the segregated with a nagging feeling of inferiority. And so many of us face that, and so many of us face it as a result of the long night of slavery and segregation. And I would like to say that in spite of this, we must work hard now to achieve excellence in our various fields of endeavor. I know the dilemma. Here we are now caught in a situation in history where we have been the victims of 344 years of slavery and segregation. And now the forces of history are saying that we must be as productive and as resourceful as individuals who have not known such oppression. This is a difficult problem. It is a real dilemma. For he who gets behind in the race must forever remain behind, or run faster than the man in front. This is the dilemma which the Negro faces in this nation today, and it is a real one. And so that means that we’ve got to work hard. We’ve got to study hard. We’ve got to go out of the way to gain new skills. We’ve got to go out of the way to burn the midnight oil. We’ve got to go out of the way to keep from dropping out of school. And I know the reasons why all of these things are done. But after we go through this sociological analysis, then we must get to the point that we are willing to work with determination to achieve excellence in our fields of endeavor. The doors are opening now that were not open to our mothers and our fathers. The great challenge facing us is to be ready to enter these doors as they open. Ralph Waldo Emerson said in a lecture back in 1871 that if a man can write a better book or preach a better sermon or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, even if he builds his house in the woods, the world will make a beaten path to his door. This will become increasingly true and so it means that we must set out to do a good job and try to do it so well that nobody could do it any better. Now don’t set out to do a good Negro job. You see we are now in a situation where we are forced to compete with people. And anybody setting out to be a good Negro you see if you set out merely to be a good Negro lawyer, or a good Negro doctor, or a good Negro school teacher, a good Negro preacher, a good Negro skilled laborer, a good Negro barber or beautician, you’ve already flunked your matriculation exam for entrance to the university of integration. We must set out to do a good job and to do that job so well that the living, the dead, or the unborn couldn’t do it any better. And so to carry to one extreme, if it falls your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures. Sweep streets like Beethoven composed music. Sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry. Sweep streets so well that all the host of heaven and earth will have to pause and say, “Here lived a great street sweeper who swept his job well.” If you can’t be a pine on the top of the hill be a scrub in the valley, but be the best little scrub on the side of the hill. Be a bush if you can’t be a tree. If you can’t be a highway, just be a trail. If you can’t be the sun, be a star, for it isn’t by size that you win or you fail. Be the best of whatever you are. And if we will do this we will remain awake through a great social revolution.

There is another thing, a thing that faces all of us. We are challenged to develop an action program all over our nation to get rid of the last vestiges of segregation and discrimination. And this problem will not work itself out, and anybody who believes that is sleeping through a revolution. If the problem of segregation and discrimination is to be removed from our nation, we must work hard in an action program to do it. Now, there are one or two ideas that I mention so often that we’ve got to get rid of. They’re myths. And if we are going to solve this problem, we’ve got to get rid of them. One is the myth of time. You’ve heard this argument. The people who believe this go on to say to the Negro and his allies in the white community that only time can solve the problem. And they go on to say if you will just be nice, and be patient, and continue to pray in a hundred or two hundred years the problem will work itself out. Now I am not criticizing prayer, certainly not, for it has been one of the great resources of my life and in the darkest moments, the moments that I have had to stand amid the surging movement of life’s restless sea, prayer has been so meaningful to me. So don’t misunderstand me. I am not saying that prayer does not have a value. But I am saying that God never intended for prayer to be a substitute for working intelligence. The only answer that we can give to those who believe in the myth of time is that time is neutral. It can be used either constructively or destructively. And I am absolutely convinced as I stand before you tonight, my friends, that the people of ill will in our nation have used time much more effectively than the people of goodwill. I am convinced tonight that the Wallace’s of our nation and the extreme rightists of our nation and those who are committed to negative ends have used time much more effectively than those who are committed to good ends. And it may well be that we will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and the violent actions of the bad people who will bomb a church in Birmingham, Alabama, but also for the appalling silence of the good people who sit around saying, “Wait on time.” Somewhere we must come to see that human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and the persistent work of dedicated individuals who are willing to be coworkers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the primitive forces of social stagnation. And so we must help time and realize that the time is always right to do right.

And I am sure you have heard the other myth. You hear it here in California and we hear it all over the nation now because of the civil rights debate. It is the idea that legislation cannot solve the problem which we face in human relations. I am sure you have heard that. People who believe in this and who set forth this argument will go on to say that the only way that this problem can be solved is through changing the heart and changing attitudes. And they say you can’t do that through legislation. Well, certainly they are uttering a half-truth. If we are to solve this problem that we face in our nation ultimately, Negroes and white people must come together as brothers and sisters, not merely because the law says it, but because it is natural and right. If this problem is to be solved ultimately, men must not only be obedient to that which can be enforced by the law. We must rise to the majestic heights of being obedient to the unenforceable. I am aware of this. But we must go on and state the other side. It may be true that you can’t legislate integration, but you can legislate desegregation. It may be true that morality cannot be legislated, but behavior can be regulated. It may be true that the law cannot change the heart but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law can’t make a man love me, but it can restrain him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important also. And so while the law may not change the hearts of men, it does change the habits of men. And when the habits are changed, pretty soon the heart will be changed and the attitudes will be changed.

And so there is a need for civil rights legislation now on the national scale and in local communities all over our nation. I would like to impress upon you this evening the importance of this. There is a debate taking place in the Senate of our nation now. And it has moved from the realm of legitimate debate. It is a filibuster. It is a filibuster clothed in the garments of gentlemanly debate, and it is time now that the Senate go on and vote on this vital bill which can do so much to restore the sense of hope in the Negro community and give the Negro new faith in the legislative and democratic process. It is urgent that this Civil Rights Bill be passed and passed very soon. Now there are those who are trying to weaken that bill. They are trying to weaken it with crippling amendments and somehow all people of goodwill through letter-writing campaigns, through visits to Washington to various Senators, and through other methods of direct action and created witnesses, to make it clear that this bill must pass. It was on a sweltering afternoon last June, and a young vigorous intelligent dedicated president stood before this nation and said in eloquent terms, “The issue which we face in civil rights is not merely a political issue. It is at bottom a moral issue.” He went on to say it is as old as the Scriptures and as modern as the Constitution. It is a question of whether we will treat our Negro brothers as we ourselves would like to be treated. And on the heels of this great speech he went and offered a civil rights package to Congress. The most comprehensive civil rights package ever presented by any president of our great nation. Since that sweltering afternoon last June, our nation has known a dark day and a dreary night, for that same president was cut down by an assassin’s bullet on Elm Street in Dallas, Texas. And I think the greatest tribute that the United States of America can pay to the late John Fitzgerald Kennedy is to see that this Civil Rights Bill is passed without being watered down at any point.

So if this bill does not pass, I am absolutely convinced that our nation will experience a dark night. If this bill does not pass, the already ugly sore of racial injustice on the body politic may suddenly turn malignant and our nation may well be inflicted with an incurable cancer that will destroy our political and moral health. It is urgent for the health of the nation for this Civil Rights Bill to be passed. And it is necessary that in local communities, and in states all over our nation, to make civil rights legislation a reality and to make its firm enforcement a reality. And right here in this state, in this great state, in this state that has meant so much to our nation, in this the most populous state of our nation, you have a great choice. It is a choice of treading the low road of injustice or remaining true to the high road of justice. You have a choice of whether you will go backward or whether you will go forward. You have a choice whether you will be true to the ideals of justice, or whether you will somehow go back and choose those principles of injustice, which will hurt our whole nation, for there are forces alive in this state seeking to repeal the Fair Housing Bill, which has existed on the books, on the statute books of California. And if this bill is repealed, it will be a setback not merely for California. It will be a setback for the nation; it will be a setback for democracy; and it will be one of the great tragedies of the 20th century. And so, I call upon each of you assembled here tonight to work passionately and unrelentingly to defeat the proposed Constitutional Housing Amendment in California. And with this, and with other forces working, I believe this can be done.

Now I do not want to give the impression that there is nothing for the Negro himself to do. The federal government can’t solve the whole problem. I said over and over again that if justice is to be a reality for the Negro in America, the Negro must feel a basic responsibility and a basic urge to struggle and sacrifice for that freedom and justice. And so this is the meaning of the movement. This is the meaning of what is taking place in our nation today. It is the meaning of the demonstrations. This is behind the freedom rides that you hear about here and there, the sit-ins, the stand-ins, the wade-ins, the kneel-ins, and all of the other “-ins.” They are all for the purpose of getting America out of the dilemma in which she finds herself as a result of the continued existence of segregation and discrimination. And I am convinced that if this problem is to be solved, we must delve deeper into strong action programs to keep the issue before the forefront of the nation.

But as I have said all across the country, I am convinced that our struggle must be a nonviolent struggle. I am convinced that our basic thrust must be nonviolent. But if the Negro succumbs to the temptation of using violence in his struggle, unborn generations will be the recipients of a long and desolate night of bitterness, and our chief legacy to the future will be an endless reign of meaningless chaos. And there is another way, a way as old as the insights of Jesus of Nazareth, and as modern as the techniques of Mohandas K. Gandhi. There is another way. A way as old as Jesus saying, “Turn the other cheek.” And as modern as Gandhi saying, through Thoreau, that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. And I believe that through this other way we will have a powerful pushing movement that will change the very structure and bring about justice and freedom. And there is power in nonviolent resistance. It has a way of disarming the opponent. It exposes his moral defenses. It weakens his morale and at the same time it works on his conscience, and he just doesn’t know how to handle it. If he doesn’t beat you, wonderful. If he beats you, you develop the quiet courage of accepting blows without retaliating. If he doesn’t put you in jail, wonderful, nobody with any sense loves to go to jail. But if he puts you in jail, you go in that jail and transform it from a dungeon of shame to a haven of freedom and human dignity. Even if he tries to kill you.

Even if he tries to kill you, you develop the inner conviction that there are some things so clear, some things so precious, so eternally true that they’re worth dying for. And if a man stands before some truth he may be 30 years old, some great principle stands at the door of his life, some great truth, some great issue, and he refuses to take a stand because he’s afraid that his home may get bombed or he’s afraid that he may lose a job or he’s afraid that he may get killed. He may go and live until he’s 80, but he’s just as dead at 30 as he will be at 80.

And in a real sense, the cessation of breathing in his life is merely the belated announcement of an earlier death of the spirit. He died when he refused to take a stand for that which is right, for that which is noble, for that which is just, and that which is true. When one is committed to this he has power, and there is another thing about this method of nonviolence. It says that it is possible to struggle to secure moral ends through moral means. One of the great debates of history has been over the whole question of ends and means. There have been those thinkers who argue that the end justifies the means. Sometimes whole systems of government have followed this theory. And I think one of the great weaknesses of the misguided philosophy of communism is right here. In so many instances in its theoretical structure, it argues that any method is justifiable in order to bring into being the goal of the end of the classless society. For this is where nonviolence would break with communism or any other system which argues that the end justifies the means. In a real sense, the end is preexistent in the means. The means represent the ideal in the making and the end in process. And in the long run of history, destructive means cannot bring about constructive ends, and it is a beautiful thing to have a method of struggle which says you can work to secure moral ends through moral means. And the other thing that is beautiful about nonviolence is that you can come to the point that you stand up against the unjust system and yet not hate the perpetrators of that unjust system. Oh, this is very difficult, but it is possible. The love ethic can stand at the center of the struggle of racial justice. So often we fail to see the danger of hate. Hate is as injurious to the hater as it is to the hated. Psychiatrists are telling us now that many of the strange things that happen in the subconscious, many of the inner conflicts, are rooted in hate. And they are saying, “Love or perish.” Well, Jesus said it a long time ago: “Love your enemies. Bless them that curse you. Pray for them that despitefully use you.” And so in some way, even though it has been very difficult, we have been able to say to our most violent opponents:

We will match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will and we will still love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws and so, throw us in jail, and we will still love you. Yes, bomb our homes and threaten our children and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities at the midnight hour and drag us out on some wayside road and beat us and leave us half-dead and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. But be you assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer and one day we will win our freedom. But we will not only win freedom for ourselves. We will so appeal to your heart and your conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.

This is a nonviolent method, and this is its philosophy. And I believe that if we will go this way, and if we will continue to stand up against the unjust system with determination, we will be able to bring into being that better day, that great America. We will be able to bring into being the brotherhood of man. And may I reiterate, this problem will not work itself out. May I say, my friends, that it is not merely a sectional problem. Many things have happened over the last few months to reveal to us that we are dealing with a national problem, and that no section of our country can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood. And it is one thing for a white person of good will outside of the South to rise up with righteous indignation when the busses burn with freedom riders in Anniston, Alabama; or when a church is bombed in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four innocent, beautiful, unoffending girls; or when a courageous James Meredith cannot go to the University of Mississippi without confronting riotous conditions. That same white person of good will outside the South must rise up with righteous indignation when a Negro cannot live in his neighborhood, or when a Negro cannot get a job in his particular firm, or when a Negro cannot join a particular fraternity, sorority, academic or professional society. If this problem is to be solved there must be a divine discontent. Somebody must come to believe this thing is so important that they are willing to give all that they have to make the brotherhood of man a reality. If this problem is to be solved, there is need for another Amos to rise up in our nation. And cry out in words echoing across the centuries, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” If this problem is to be solved, there is need for another Abraham Lincoln to see that this nation cannot survive half slave and half free. If this problem is to be solved, there is need for another Jefferson to see in the midst of an age amazingly adjusted to slavery and in words lifted to cosmic proportions, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights.” If this problem is to be solved, somebody must say, with Jesus of Nazareth, “He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword.” And when we come to see this, we will be able to emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man’s inhumanity to man, into the bright and glittering daybreak of freedom and justice. This is our challenge, and this is our responsibility.

And may I say to you, my friends, that I still have faith in the future. I know these are difficult moments and so many of us are faced with problems day in and day out. And I know that we are still at the bottom of the economic ladder, still the last hired and the first fired. I know that we are forced to stand amidst conditions of oppression, trampled over day in and day night by the iron feet of injustice. But in spite of this, I still believe that we have the resources in this nation to solve this problem and that we will solve this problem. And so I can still sing our theme song, “We shall overcome, we shall overcome, deep in my heart I do believe, we shall overcome before the victory’s won.” Before the victory is won some more will be scarred up a bit, but we shall overcome. Before the victory for justice is won, some more will have to be thrown into dark and lonesome jail cells, but we shall overcome. Before the victory is won, some will be misunderstood and called bad names. Some will be called “communists” and “red” simply because they believe in the brotherhood of man, but we shall overcome. Before the victory is won, somebody else like a Medgar Evers may have to face physical death, but if physical death is the price that some must pay to free their children from a permanent psychological death, then nothing can be more redemptive. Yes, we shall overcome. And I’ll tell you why. Because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. We shall overcome because Carlisle is right, “No lie can live forever.” We shall overcome because William Cullen Bryant is right, “Truth crushed to earth will rise again.” We shall overcome because James Russell Lowell is right, “Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne. Yet that scaffold sways the future and behind the dim unknown standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch upon his own.” We shall overcome because the Bible is right, “You shall reap what you sow.” And so with this faith, we will be able to hew out of this mountain of despair the stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. This is the challenge!

And so I leave you tonight by saying, work with this movement, support this movement, struggle for this movement, knowing that in struggling for freedom and justice and human dignity, you are being a coworker with God. Stand up for justice, not next week, not even tomorrow, not even an hour from now, but at this moment, realizing a tiny little minute, just sixty seconds in it, I didn’t choose it, I can’t refuse it, it’s up to me to use it. A tiny little minute, just sixty seconds in it, but eternity is in it. God bless you.