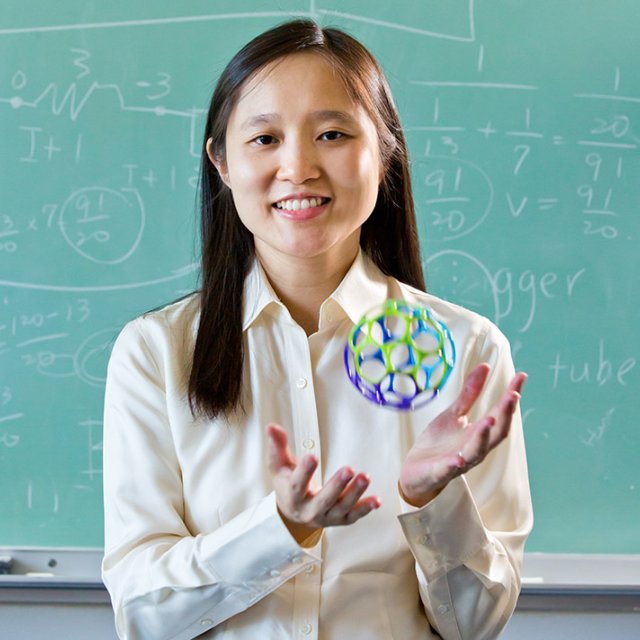

To explain her field of study, Dr. Michelle Chen, PLNU associate professor of physics, refers to a ball on her desk. It is hand-sized and made up of hexagons, like a soccer ball you can see all the way through. She points to each part and explains: each intersection of lines symbolizes a carbon atom and each line is a bond between them.

It’s a visual representation of a carbon buckyball – the angstrom-sized (one ten-billionth of a meter), perfectly round molecule. If that ball were to be laid out flat and rolled back up into a cylinder, it would represent a carbon nanotube. The carbon nanotube is what Chen has been studying since her days in graduate school, and it’s what her students at PLNU dedicate much of their time researching as well. For its complexity and practical applications, it fits Chen’s strengths and proclivities.

“I was always interested in science,” said Chen. “In high school, I was really interested in superconductors and levitation trains.”

Her atypical interests only strengthened throughout high school as she decided she would study physics. In college, she narrowed her sights to experimental physics, which focuses more on data acquisition and hands-on exploration than theoretical prediction and explanation of physics concepts. After earning her undergraduate and master’s degrees in physics at the University of Chicago, she earned her Ph.D. in material science and engineering from the University of Pennsylvania.

“I thought physics would be a good thing to study to understand how things work,” said Chen.

That explains her penchant for tangible models to explain complex topics, like the carbon nanotube.

“Physics is quite broad,” said Chen. “I was always more interested in the application of unique and tangible materials.”

And there are many applications for the nanotube. It can be thought of as a rolled-up structure of graphene, a crystalline form of carbon with that hexagonal arrangement of molecules. Its composition makes it extremely light but very strong, as well as an excellent conductor of heat and electricity.

“In theory, it’s the perfect material,” said Chen.

For these reasons and others, Chen has led a select group of physics and engineering students for the past three summers. Chen’s research students have teamed up with PLNU’s chemistry and biology departments as well as researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital to study how nanomaterials such as graphene and the carbon nanotube affect biological systems. Chen explains an example in the field of medicine:

“Many people ask how to deliver drugs into the body, but not many ask how it affects the body afterward — how cells grow, die, etc. This type of research asks those questions.”

She has recently led a group of eight students who partnered with Dr. Sara Choung, PLNU professor of chemistry, to grow graphene and carbon nanotubes in a furnace to study them under electron microscopes and watch how they behave. Last summer, Chen and her students partnered with Dr. Mike Dorrell, PLNU associate professor of biology, to grow brain tumor cells on graphene and watch how they behaved. For burgeoning fields like tissue engineering, where scientists use materials like graphene as scaffolding to grow cells, this type of study is invaluable.

Since physics and engineering majors at PLNU research collaboratively with the chemistry and biology departments, students in each area of expertise are playing an active role in helping to solve problems and come up with practical applications in different science fields.

This approach not only bridges departments, but it also combines, at a deeper level, the things Chen loves most about her job as a professor – collaboration and relationships.

“Students really enjoy the fellowship here. They feel at home,” said Chen. “And it was always in my mind to teach in a small environment. I really wanted to bring undergraduates into the research.”

Coming from her previous position as professor of physics at Simmons College, a small women’s university in Boston, she is particularly drawn to encouraging women who study and work in the sciences, especially physics. At PLNU, she’s seen that population grow in her department, something that encourages her in light of her own college experience as a student.

“In college and graduate school, I would often be one of the few women in a 100-person lecture hall,” said Chen.

With her gender underrepresented in growing science fields, she is playing a vital role by inspiring and equipping young women (as well as men) who identify passion in the sciences. The inspiration goes both ways.

“The students here have so much talent,” said Chen. “It’s rewarding for me that I get to know them not just academically but [also personally as I learn] about their lives, their struggles, and their faith.”

The Viewpoint

PLNU's university publication, the Viewpoint, seeks to contribute relevant and vital stories that grapple with life's profound questions from a uniquely Christian perspective. Through features, profiles, and news updates, the Viewpoint highlights stories of university alumni, staff, faculty, and students who are pursuing who they are called to be.